To the left, Sachin Ramesh Tendulkar dressed up in a nice suit, hair all well done, sporting a genial smile as always, empty arms drawn forward to receive. To the right, Pranab Mukherjee, the 13th President of the Republic of India, in his regular Nehru suit, hands stocked with a scroll of honour, was all set to give.

The next few moments, as the scroll changed hands from President to cricketer, from authority to civilian, marked a significant moment in the history of civilian honours in India.

For the first time in the country’s history, a sportsperson had been awarded the country’s highest civilian honour. For decades to come, when people look back at the person who was the first to break the trend, the name of Sachin Tendulkar will reverberate loudly. Just about the perfect picture, right, for a man believed to be the greatest batsman and greatest cricketer of his generation, with some sections even stretching the narrative beyond the generational boundary to all of time?

Turns out it’s not as perfect a picture as it seems.

Tendulkar, of course, is no stranger to awards. The man is an exceptional talent and has been bagging awards by the truckloads ever since he started playing cricket. He would probably require an entire house just to stock the various awards he has received through his long career, maybe even two. There is no disputing his credentials as one of the finest cricketers of his generation.

But just as the ‘Bharat Ratna for Sachin’ campaign ushered in by millions of his fans and flippant media houses gained momentum, at the other end of the spectrum, sections of sportsmen and other regular citizens decided to crank up the volume on why they felt that hockey wizard Dhyan Chand deserved the Bharat Ratna ahead of Tendulkar. It sounds like a very valid point, but before we go into the intricacies of comparing the achievements of these two gifted mortals, it is important to understand the lead actor at the centre of it all.

The Bharat Ratna – what does the award represent?

The ‘Jewel of India’ is the Republic of India’s highest civilian award. For the record, the second highest is the Padma Vibhushan, the third highest the Padma Bhushan and the fourth highest, the Padma Shri. C.N.R. Rao and Sachin Tendulkar became the 42nd and 43rd persons respectively to receive the honour of the Bharat Ratna, following in the footsteps of 42 other individuals that includes foreign nationals such as Nelson Mandela and Mother Teresa (the award is not restricted to Indian nationals alone).

The other significant thing about the Bharat Ratna is that a maximum of three awards can be made in a single year. And, as has probably been well known by now, the award wasn’t open to sportspersons until 2011; the stipulation before 2011 specified that the award was to be conferred “for the highest degrees of national service. This service includes artistic, literary, and scientific achievements, as well as “recognition of public service of the highest order.”

An amendment to this stipulation was made in December 2011 in order to enable sportspersons to be eligible for the award with the rule now allowing the award to be conferred “for performance of highest order in any field of human endeavour.”

Amongst other things that the award decrees on its holder is the seventh highest rank in the Indian order of precedence as far as ceremonial protocol is considered (no legal standing), behind only the President, Vice-President, Prime Minister, Governors of States, former Presidents, the Deputy Prime Minister, the Chief Justice of India, and the Speaker of the Lok Sabha.

Now that is some rarefied airspace indeed.

Perhaps the most important aspect of all that needs to be remembered is that the award is based on the recommendation of the Prime Minister’s Office.

How did sport enter the Bharat Ratna discussion?

As mentioned earlier, the amendment to expand the scope of the award to any and every field came about in 2011. The move, while welcome, and a strong source of encouragement to sportspersons in the country, does leave some questions as to why it took the 11th year of the 21st century for a country’s decision makers to bring about this change, for there has been no shortage of Indian sportspersons with stupendous achievements in all these years.

It could be argued that the move was made keeping Tendulkar in mind, and his possible coronation in the immediate aftermath of his impending retirement. But leaving aside sportspersons from other fields, there have been several other cricketers who have been more than deserving of the Bharat Ratna. There is Kapil Dev, who was special in his own right; perhaps the greatest all-rounder that India has produced till date and the captain that delivered the country’s first ever World Cup. His career definitely does classify as a ‘performance of the highest endeavour’. Or for that matter, even the careers of Sunil Gavaskar and Rahul Dravid (considering he retired earlier) do.

And when it comes to other sports – there’s Viswanathan Anand and Dhyan Chand.

It is now the right time we got introduced to the convulsive coming together of popular opinion, pandering and politics.

The Tendulkar decision

As the response drawn by the Right To Information (RTI) query filed by sports enthusiast Hemant Dube showed, haste underlined the decision of the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO) in setting up the recommendation for Tendulkar to receive the award.

The process was set in motion on November 14, 2013, coinciding in perfect fashion with the beginning of the ‘Master Blaster’s’ final Test in his hometown of Mumbai. As India went about putting the finishing touches to another home Test win, the process of him receiving the Bharat Ratna was being cemented with much alacrity.

The move smacked of slandering to an emotional groundswell of public emotion. It seemed like a desperate attempt for salvation by a ruling government in the doldrums going into election year and rocked by accusations of failed governance, in the hope that it would alleviate some of the beating that its image had taken in the public eye.

It is very easy to be swayed in today’s times by an event such as the retirement of Tendulkar, what with the extensive media coverage and social media outlets bombarding public thought and feeding off shared dogma while hardly leaving room for individual opinions and self thought.

The Hall of Fame – Sachin Tendulkar, Viswanathan Anand and Dhyan Chand

Sachin Tendulkar, the Little Master

When one talks of Tendulkar, some of the things that instantly stand out are his longevity and his ability to play through not one, not two, but three generations. His skills as a batsman apart, what distinguished him was his dedication, hard work and continued zest to look out for improvements. Many have the talent, but few bring it to fruition and stay consistent at it, and that’s something that Tendulkar managed very well.

That said, many of his numbers are a sheer product of his longevity, so comparing them to prove his superiority over others is a little dubious. And the comparison across generations begs absolutely no merit, because quite frankly, one generation would in most cases be biased towards the champion of their era.

Tendulkar was named the Wisden Cricketer of the Year in 1997, the Player of the Tournament at the 2003 ICC ODI World Cup, the Wisden Leading Cricketer in the World in 2010, was given the Wisden India Outstanding Achievement award in 2012 and was named an Honorary Member of the Order of Australia by the Australian government that same year.

He was presented the Arjuna Award in 1994 and the Rajiv Gandhi Khel Ratna award in 1997-98. Now, along with the Bharat Ratna, he holds three out of the four highest civilian honours in India – the highest (Bharat Ratna 2014), the second highest (Padma Vibhushan 2008) and the fourth highest (Padma Shri 1999).

Viswanathan Anand, The Lightning Kid

As far as talk of champion sportspersons from India is concerned, the talk is never complete without including Viswanthan Anand, who for over two and a half decades has competed at the very top in the world of chess, fending off competitors senior to him, of his age as well as those junior to him. The last memory one may have of Anand might be the hammering he received at the hands of Magnus Carlsen in the their World Chess Championship match in Chennai, but that should in no way take the sheen off of the career of one of the world’s premier chess Grand Masters.

Anand was a 5-time World Chess Champion and the World Rapid Chess champion in 2003, apart from holding the number one ranking numerous times between 2007 and 2011. In a country where there have hardly been other number one’s in any individual sport, Anand’s reign is exemplary. In fact, in October 2008 he dropped out of the top three for the first time since July 1996. Chess players, both former and current, rate him as amongst the strongest rapid player of his time. He has received the Chess Oscar six times and is one of only six players in the history of the sport to have broken the 2800 Elo rating barrier of the FIDE rankings.

Experts consider Anand to be one of the most versatile players of all time, considering that he won World Championships in different formats. And Vladimir Kramnik, a long time adversary of Anand’s, had said in an interview in 2011: “I always considered him to be a colossal talent, one of the greatest in the whole history of chess, and I think that in terms of play Anand is in no way weaker than Kasparov but he’s simply a little lazy, relaxed and only focuses on matches.”

Anand too was presented the Arjuna Award in 1985 and was the first recipient of the Rajiv Gandhi Khel Ratna award, in 1991-92. Like Tendulkar, he too holds three of the four highest civilian honours – the Padma Vibhushan (2007), the Padma Bhushan (2000) and the Padma Shri (1987).

Dhyan Chand, the Hockey Wizard

Boasting superb dribbling skills, ball-control and goal scoring ability of the highest order, Dhyan Chand was a hockey player who, like Anand and Tendulkar after him, captured the attention of not just the country, but of the entire international community, in the process earning the nickname, ‘The Hockey Wizard’.

Three successive gold medals (1928, 1932, 1936) as part of a dominant Indian hockey team at the time and over 400 international goals and 1000 overall added some serious glow to a career that wasn’t short on glitter thanks to his superb stick work.

Chand has a statue in his honour in Vienna, Austria, which is in the form of a man with four hands and a stick in each, depicting his legendary control over the ball. Along with almost 358 other Olympic heroes, he had a tube station in London named after him in the run-up to the 2012 Olympics.

He retired from competitive hockey in 1948, but it was when he retired from his post as Major in the Indian Army in 1956, that the Government of India moved to present him the nation’s third highest civilian honour, the Padma Bhushan. The maestro’s birthday, August 29, is celebrated as National Sports Day, and is the day when sports-related awards such as the Arjuna, Rajiv Gandhi Khel Ratna and Dronacharya awards are presented.

The National Hockey Stadium in Delhi, in 2002, was renamed the Dhyan Chand National Stadium, and now plays host to most international tournaments in India. Not just that, the year also saw an award being instituted in his name to recognize sportspersons for not just their superb performances through their career, but also their contributions after retirement, just as Chand had done.

The real debate – has justice been done by making Tendulkar the first sportsperson to receive the honour?

Contrary to what many may perceive, the debate is not about who is the greatest amongst the three, or who is the most deserving. It was never about a slug fest between these three champions of their respective sports.

It boils down to a question of the institution of the Bharat Ratna being opened up to sportspersons and being fair in its dealings in order to make up for all those who suffered under its oversight all these years.

The popularity of cricket over chess and hockey has played a significant role in Tendulkar becoming the first sportsperson to receive this honour. For all you know, had the amendment been made in the 1940s, Dhyan Chand may well have got the honour because of the popularity of hockey at that time.

As in the case of the previous awards that the three men have received, Anand received the Padma Shri first in 1987, followed by Tendulkar in 1999. Likewise, the Padma Vibhushan went to Anand in 2007 and Tendulkar in 2008. Anand’s three honours were spread out over a course of 20 years while Tendulkar’s three have been spread out over the last 15 years. Chand probably never was considered for the Padma Vibhushan due to the step-motherly treatment that sports received at the time. Can the disconnect possibly be more obvious?

The Anand and Chand camps would be well within their rights to question the fairness of what happened today. It’s not Chand’s fault that hockey is not as popular as cricket today, nor is it Anand’s mistake that a majority of the people in the country either don’t have the patience for chess, or don’t understand it. Why, then, should Chand and Anand be considered less deserving of the honour?

What’s important to realize here is that Tendulkar is in no way the villain in the piece. He is just a sportsperson who went about doing his business, and was pounced upon by the machinations of an opportunistic government looking to win a few brownie points by using him as a pawn in their political chessboard. And comparing him to previous recipients such as Homi Bhaba, C.V. Raman, A.P.J. Abdul Kalam and engaging in a street fight over their accomplishments for the greater good is pointless, because quite simply it is difficult to compare things that are as dissimilar as chalk and cheese.

Tendulkar may very well be deserving of the honour. However, what doesn’t quite seem right is the fact that he got it first.

And to all those who maintain that the timing of the award is inconsequential as long as Chand and Anand get their due recognition in the years to come, how about a small example.

In the company that you work, if you were overlooked for a promotion while being a very deserving candidate, and a few years later you noticed that another employee of similar ilk was given one at a much earlier stage than you were, would it be just?

If you filed a case fighting for some gross injustice done to you, and while waiting countless years for justice, you notice that a similar case filed much later than yours, lasting fewer years in duration, was provided a verdict faster, would it not cause indignation within you? Would it be fair?

The next few moments, as the scroll changed hands from President to cricketer, from authority to civilian, marked a significant moment in the history of civilian honours in India.

Indian cricketer Sachin Tendulkar (L) receives the Bharat Ratna award from Indian President Pranab Mukherjee during an awards ceremony at the Presidential Palace on February 4, 2014 in New Delhi, India.

For the first time in the country’s history, a sportsperson had been awarded the country’s highest civilian honour. For decades to come, when people look back at the person who was the first to break the trend, the name of Sachin Tendulkar will reverberate loudly. Just about the perfect picture, right, for a man believed to be the greatest batsman and greatest cricketer of his generation, with some sections even stretching the narrative beyond the generational boundary to all of time?

Turns out it’s not as perfect a picture as it seems.

Tendulkar, of course, is no stranger to awards. The man is an exceptional talent and has been bagging awards by the truckloads ever since he started playing cricket. He would probably require an entire house just to stock the various awards he has received through his long career, maybe even two. There is no disputing his credentials as one of the finest cricketers of his generation.

But just as the ‘Bharat Ratna for Sachin’ campaign ushered in by millions of his fans and flippant media houses gained momentum, at the other end of the spectrum, sections of sportsmen and other regular citizens decided to crank up the volume on why they felt that hockey wizard Dhyan Chand deserved the Bharat Ratna ahead of Tendulkar. It sounds like a very valid point, but before we go into the intricacies of comparing the achievements of these two gifted mortals, it is important to understand the lead actor at the centre of it all.

The Bharat Ratna – what does the award represent?

The ‘Jewel of India’ is the Republic of India’s highest civilian award. For the record, the second highest is the Padma Vibhushan, the third highest the Padma Bhushan and the fourth highest, the Padma Shri. C.N.R. Rao and Sachin Tendulkar became the 42nd and 43rd persons respectively to receive the honour of the Bharat Ratna, following in the footsteps of 42 other individuals that includes foreign nationals such as Nelson Mandela and Mother Teresa (the award is not restricted to Indian nationals alone).

The other significant thing about the Bharat Ratna is that a maximum of three awards can be made in a single year. And, as has probably been well known by now, the award wasn’t open to sportspersons until 2011; the stipulation before 2011 specified that the award was to be conferred “for the highest degrees of national service. This service includes artistic, literary, and scientific achievements, as well as “recognition of public service of the highest order.”

An amendment to this stipulation was made in December 2011 in order to enable sportspersons to be eligible for the award with the rule now allowing the award to be conferred “for performance of highest order in any field of human endeavour.”

Amongst other things that the award decrees on its holder is the seventh highest rank in the Indian order of precedence as far as ceremonial protocol is considered (no legal standing), behind only the President, Vice-President, Prime Minister, Governors of States, former Presidents, the Deputy Prime Minister, the Chief Justice of India, and the Speaker of the Lok Sabha.

Now that is some rarefied airspace indeed.

Perhaps the most important aspect of all that needs to be remembered is that the award is based on the recommendation of the Prime Minister’s Office.

How did sport enter the Bharat Ratna discussion?

As mentioned earlier, the amendment to expand the scope of the award to any and every field came about in 2011. The move, while welcome, and a strong source of encouragement to sportspersons in the country, does leave some questions as to why it took the 11th year of the 21st century for a country’s decision makers to bring about this change, for there has been no shortage of Indian sportspersons with stupendous achievements in all these years.

It could be argued that the move was made keeping Tendulkar in mind, and his possible coronation in the immediate aftermath of his impending retirement. But leaving aside sportspersons from other fields, there have been several other cricketers who have been more than deserving of the Bharat Ratna. There is Kapil Dev, who was special in his own right; perhaps the greatest all-rounder that India has produced till date and the captain that delivered the country’s first ever World Cup. His career definitely does classify as a ‘performance of the highest endeavour’. Or for that matter, even the careers of Sunil Gavaskar and Rahul Dravid (considering he retired earlier) do.

And when it comes to other sports – there’s Viswanathan Anand and Dhyan Chand.

It is now the right time we got introduced to the convulsive coming together of popular opinion, pandering and politics.

The Tendulkar decision

As the response drawn by the Right To Information (RTI) query filed by sports enthusiast Hemant Dube showed, haste underlined the decision of the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO) in setting up the recommendation for Tendulkar to receive the award.

The process was set in motion on November 14, 2013, coinciding in perfect fashion with the beginning of the ‘Master Blaster’s’ final Test in his hometown of Mumbai. As India went about putting the finishing touches to another home Test win, the process of him receiving the Bharat Ratna was being cemented with much alacrity.

The move smacked of slandering to an emotional groundswell of public emotion. It seemed like a desperate attempt for salvation by a ruling government in the doldrums going into election year and rocked by accusations of failed governance, in the hope that it would alleviate some of the beating that its image had taken in the public eye.

It is very easy to be swayed in today’s times by an event such as the retirement of Tendulkar, what with the extensive media coverage and social media outlets bombarding public thought and feeding off shared dogma while hardly leaving room for individual opinions and self thought.

The Hall of Fame – Sachin Tendulkar, Viswanathan Anand and Dhyan Chand

Sachin Tendulkar, the Little Master

When one talks of Tendulkar, some of the things that instantly stand out are his longevity and his ability to play through not one, not two, but three generations. His skills as a batsman apart, what distinguished him was his dedication, hard work and continued zest to look out for improvements. Many have the talent, but few bring it to fruition and stay consistent at it, and that’s something that Tendulkar managed very well.

That said, many of his numbers are a sheer product of his longevity, so comparing them to prove his superiority over others is a little dubious. And the comparison across generations begs absolutely no merit, because quite frankly, one generation would in most cases be biased towards the champion of their era.

Sachin Tendulkar batting for India against the Minor Counties XI at Trowbridge, 12th July 1990. The match ended in a draw.

Tendulkar was named the Wisden Cricketer of the Year in 1997, the Player of the Tournament at the 2003 ICC ODI World Cup, the Wisden Leading Cricketer in the World in 2010, was given the Wisden India Outstanding Achievement award in 2012 and was named an Honorary Member of the Order of Australia by the Australian government that same year.

He was presented the Arjuna Award in 1994 and the Rajiv Gandhi Khel Ratna award in 1997-98. Now, along with the Bharat Ratna, he holds three out of the four highest civilian honours in India – the highest (Bharat Ratna 2014), the second highest (Padma Vibhushan 2008) and the fourth highest (Padma Shri 1999).

Viswanathan Anand, The Lightning Kid

As far as talk of champion sportspersons from India is concerned, the talk is never complete without including Viswanthan Anand, who for over two and a half decades has competed at the very top in the world of chess, fending off competitors senior to him, of his age as well as those junior to him. The last memory one may have of Anand might be the hammering he received at the hands of Magnus Carlsen in the their World Chess Championship match in Chennai, but that should in no way take the sheen off of the career of one of the world’s premier chess Grand Masters.

India’s Vishwanathan Anand at a press conference in State Tretyakovsky Gallery in Moscow on May 10, 2012 before his FIDE World chess championship match against Israel’s Boris Gelfand.

Anand was a 5-time World Chess Champion and the World Rapid Chess champion in 2003, apart from holding the number one ranking numerous times between 2007 and 2011. In a country where there have hardly been other number one’s in any individual sport, Anand’s reign is exemplary. In fact, in October 2008 he dropped out of the top three for the first time since July 1996. Chess players, both former and current, rate him as amongst the strongest rapid player of his time. He has received the Chess Oscar six times and is one of only six players in the history of the sport to have broken the 2800 Elo rating barrier of the FIDE rankings.

Experts consider Anand to be one of the most versatile players of all time, considering that he won World Championships in different formats. And Vladimir Kramnik, a long time adversary of Anand’s, had said in an interview in 2011: “I always considered him to be a colossal talent, one of the greatest in the whole history of chess, and I think that in terms of play Anand is in no way weaker than Kasparov but he’s simply a little lazy, relaxed and only focuses on matches.”

Anand too was presented the Arjuna Award in 1985 and was the first recipient of the Rajiv Gandhi Khel Ratna award, in 1991-92. Like Tendulkar, he too holds three of the four highest civilian honours – the Padma Vibhushan (2007), the Padma Bhushan (2000) and the Padma Shri (1987).

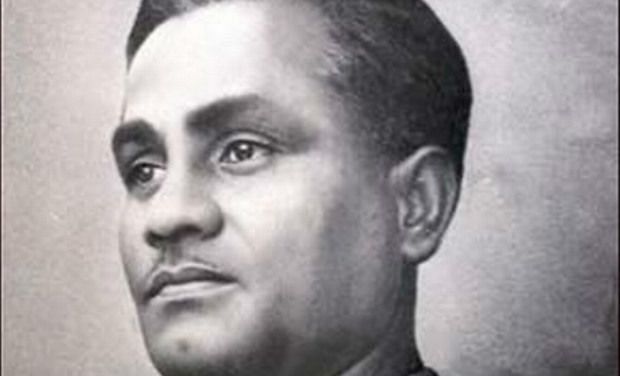

Dhyan Chand, the Hockey Wizard

Boasting superb dribbling skills, ball-control and goal scoring ability of the highest order, Dhyan Chand was a hockey player who, like Anand and Tendulkar after him, captured the attention of not just the country, but of the entire international community, in the process earning the nickname, ‘The Hockey Wizard’.

Three successive gold medals (1928, 1932, 1936) as part of a dominant Indian hockey team at the time and over 400 international goals and 1000 overall added some serious glow to a career that wasn’t short on glitter thanks to his superb stick work.

Chand has a statue in his honour in Vienna, Austria, which is in the form of a man with four hands and a stick in each, depicting his legendary control over the ball. Along with almost 358 other Olympic heroes, he had a tube station in London named after him in the run-up to the 2012 Olympics.

He retired from competitive hockey in 1948, but it was when he retired from his post as Major in the Indian Army in 1956, that the Government of India moved to present him the nation’s third highest civilian honour, the Padma Bhushan. The maestro’s birthday, August 29, is celebrated as National Sports Day, and is the day when sports-related awards such as the Arjuna, Rajiv Gandhi Khel Ratna and Dronacharya awards are presented.

The National Hockey Stadium in Delhi, in 2002, was renamed the Dhyan Chand National Stadium, and now plays host to most international tournaments in India. Not just that, the year also saw an award being instituted in his name to recognize sportspersons for not just their superb performances through their career, but also their contributions after retirement, just as Chand had done.

The real debate – has justice been done by making Tendulkar the first sportsperson to receive the honour?

Contrary to what many may perceive, the debate is not about who is the greatest amongst the three, or who is the most deserving. It was never about a slug fest between these three champions of their respective sports.

It boils down to a question of the institution of the Bharat Ratna being opened up to sportspersons and being fair in its dealings in order to make up for all those who suffered under its oversight all these years.

The popularity of cricket over chess and hockey has played a significant role in Tendulkar becoming the first sportsperson to receive this honour. For all you know, had the amendment been made in the 1940s, Dhyan Chand may well have got the honour because of the popularity of hockey at that time.

As in the case of the previous awards that the three men have received, Anand received the Padma Shri first in 1987, followed by Tendulkar in 1999. Likewise, the Padma Vibhushan went to Anand in 2007 and Tendulkar in 2008. Anand’s three honours were spread out over a course of 20 years while Tendulkar’s three have been spread out over the last 15 years. Chand probably never was considered for the Padma Vibhushan due to the step-motherly treatment that sports received at the time. Can the disconnect possibly be more obvious?

The Anand and Chand camps would be well within their rights to question the fairness of what happened today. It’s not Chand’s fault that hockey is not as popular as cricket today, nor is it Anand’s mistake that a majority of the people in the country either don’t have the patience for chess, or don’t understand it. Why, then, should Chand and Anand be considered less deserving of the honour?

What’s important to realize here is that Tendulkar is in no way the villain in the piece. He is just a sportsperson who went about doing his business, and was pounced upon by the machinations of an opportunistic government looking to win a few brownie points by using him as a pawn in their political chessboard. And comparing him to previous recipients such as Homi Bhaba, C.V. Raman, A.P.J. Abdul Kalam and engaging in a street fight over their accomplishments for the greater good is pointless, because quite simply it is difficult to compare things that are as dissimilar as chalk and cheese.

Tendulkar may very well be deserving of the honour. However, what doesn’t quite seem right is the fact that he got it first.

And to all those who maintain that the timing of the award is inconsequential as long as Chand and Anand get their due recognition in the years to come, how about a small example.

In the company that you work, if you were overlooked for a promotion while being a very deserving candidate, and a few years later you noticed that another employee of similar ilk was given one at a much earlier stage than you were, would it be just?

If you filed a case fighting for some gross injustice done to you, and while waiting countless years for justice, you notice that a similar case filed much later than yours, lasting fewer years in duration, was provided a verdict faster, would it not cause indignation within you? Would it be fair?

Justice delayed is justice denied. And the fact that neither Dhyan Chand nor Viswanathan Anand were conferred the Bharat Ratna before Tendulkar was, is as fine an example of that saying as any you could possibly find.

No comments:

Post a Comment